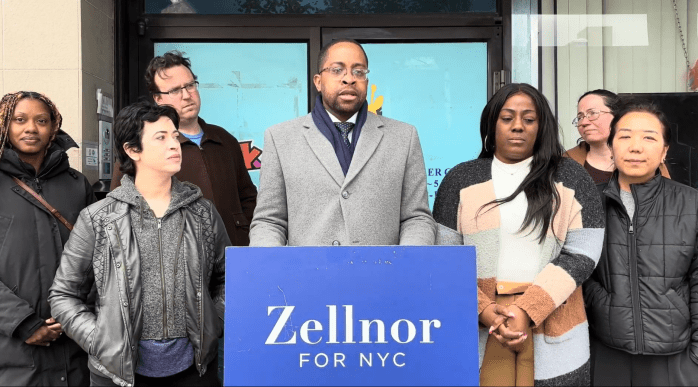

A self-proclaimed progressive prosecutor, Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez is heading into his bid for reelection unopposed in the June Democratic primary. After two successive state and federal election cycles heavily focused on crime, why is Gonzalez cruising to another term without facing the blowback that his colleague in Manhattan Alvin Bragg has been up against?

Gonzalez believes it’s about his pragmatic vision of reform.

Unlike Bragg and Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, Gonzalez has not built up much of a national profile for his status as a progressive prosecutor. Though he has embraced a system that considers non-jail resolutions at every juncture of a criminal case, and expanded a conviction integrity unit — which targets faulty NYPD investigations that resulted in false convictions — Gonzalez maintains he’s not an ideologue.

“It’s not coming from an ideological place. It’s coming from trying to be smart on crime, trying to be pragmatic about how we do this work,” Gonzalez said.

A fundamental departure from the approach of other progressives is that Gonzalez avoids categorical promises about how he’s approaching different cases. This strategy stands in stark contrast to the way that Bragg, for instance, started his tenure with a “Day One Memo” distributed to his office indicating he would stop prosecuting a host of low-level crimes and would not seek bail for others. Swift backlash ensued.

Gonzalez said he takes an individual approach on each case.

“We have to make individual determinations about whether or not the prosecution of the case improves public safety and is consistent with how we as law enforcement want to interact with our community,” Gonzalez told amNY Law. “I did not join other progressives when they had the day one memos, or the ‘I will never prosecute this’ and I’ve been critical of that approach. Because my law enforcement strategy has always been about the individual being accused before the court. Are they a driver of crime?”

A case-by-case basis:

This approach also means it can be hard to pin down exactly where Gonzalez draws the line on certain types of crimes. Take fare evasion, for example. The head of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority recently called on district attorneys to aggressively prosecute fare beaters. When he first took office in 2017, Bragg’s predecessor Cyrus R. Vance Jr., announced that the Manhattan DA’s office would no longer pursue criminal cases against most people arrested over fare evasion. Gonzalez told reporters at the time he would pursue a similar policy.

Gonzalez told amNY Law there are considerations that would make him less likely to prosecute fare evaders but stopped short of making guarantees.

“If someone is a first time offender and the first time they’ve ever been arrested, or they’re a young person, I think the approach should be different towards them. As it relates to fare evasion, I don’t have a per se policy that I never prosecute,” he said. “In fact, the policy of the DA’s office is that we do prosecute people for fare evasion who are repeat offenders. And we do prosecute the sort of the transit recidivist who are causing havoc in our subways.”

He added that if there’s evidence that the fare evasion was a crime of poverty that would also be a consideration to dismiss the charges. But beyond the moral angle, a considerable part of his thinking on this issue is the bottom line of bringing fare evasion cases forward, Gonzalez said. Each one costs around $1,000 in police, court and DA resources, all together.

“From a real fiscal standpoint, New Yorkers also have to understand that is a tremendous money-suck if it’s not gonna keep you safe,” he said.

Another progressive practice that Gonzalez originally unveiled in 2017 that has become increasingly important as federal authorities have cracked down on immigration is a policy safeguarding some immigrants charged with misdemeanors or nonviolent crimes from deportation when possible. Gonzalez said he was among the first DAs in the country to hire immigration attorneys to advise his staff on how to avoid charging and prosecuting immigrants with legal status with crimes that could automatically lead to deportation.

The fundamental question, Gonzalez said, is whether there is “any way we can work out something that would at least give [the legal immigrant] a fighting chance in immigration court?”

But like fare evasion, the moves that Gonzalez’s office takes to help reduce deportations is case-based. “If we can, we can,” he said. “If we can’t, we can’t.”

It also offers no promise to undocumented immigrants. “If you have no legal status in the United States at all, my collateral consequence policy does not protect you because the government can choose to deport you whenever they want to because you don’t have status,” Gonzalez said.

Brooklyn state of mind:

Gonzalez came to the Brooklyn District Attorney’s Office immediately after law school as a junior prosecutor in the ‘90s and has been working there since. The fact that he has spent his entire career at the same office watching his predecessors operate has informed his thinking.

“I’m a career prosecutor,” he said. “So I’ve been in the trenches. I’ve done every job in this office. I started as an intern. I was a paralegal… Again, never thinking that I was gonna be elected district attorney but I’ve spent a lot of years working to keep people safe. So I have a real record of working closely with law enforcement to prosecute cases.”

He lives in East New York, the neighborhood where he grew up — another part of his background that he said has helped him build trust with Brooklynites who are most impacted by the work of the Brooklyn District Attorney’s office.

“This concept of understanding the need to feel safe is what motivated me to join the DA’s office. But really, it is a fundamental understanding of the role — of what I need to do in this office,” he said.

Gonzalez became Brooklyn’s first Latino district attorney after the 2016 death of his predecessor Ken Thompson, who was the first African American elected to the office three years earlier. Gonzalez had served as chief assistant district attorney to Thompson, who abruptly died from cancer shortly after he announced that he would have to take a leave from the office. Gonzalez was then appointed the acting replacement, with the blessing of Thompson’s widow, and won the next year’s election, by a large margin.

“I believe that people who had lived life experiences in difficult neighborhoods needed to be in law enforcement institutions, that people who actually had lived in those communities and had skin in the game needed to be in these roles. I never imagined being a district attorney. That’s a different thing, but I knew that I would have some input and some influence as a prosecutor,” he said.

A holistic view of law enforcement as starting with an investment in community services has been beneficial for his office, Gonzalez said. In January he sent out a press release trumpeting that 2024 was the safest year for gun violence in Brooklyn’s history, with the fewest shooting incidents and shooting victims besting previous lows from 2019.

He attributes this success to two factors: a targeted approach toward violent crime and coordination with community organizations.

“One percent of our population is responsible for 60 percent of the violence in our city,” he said. “So when I do a gang take down, I’m not trying to arrest every kid who lives in the housing development. I’m trying to arrest the people who are engaged in the violence.”

But when shootings began to skyrocket after the Covid rippled through the city, Gonzalez said that he was confident that continuing to use the community resources tactics he had been implementing.

“I don’t think all of the reasons why Brooklyn is doing well is just because of enforcement and prosecution. We have a lot of community stakeholders and not-for-profits… It’s the violence interrupters. We have a lot of people who are engaged in moving us forward in ways that keep us safe. And I think all of those things matter and why things shot up during Covid is because none of those other things were happening,” he said.

This budget season Gonzalez has found himself in the position of joining a coalition consisting of Governor Kathy Hochul and every DA in the state to soften reforms of New York’s discovery laws, one of the sweeping criminal justice areas that the New York Legislature reformed in 2019. Across the city’s DA offices, the case dismissal rate increased from 42% in 2019 to 62% in 2023.

Hochul has proposed changing the discovery reform that required prosecutors to share evidence with defense lawyers on an accelerated timeline or face sanctions including the possible dismissal of the case. Though on the surface the effort is an instance of prosecutors uniting to scale back a criminal justice reform, Gonzalez insisted that the reforms would be a “smoothing out” of a law that he said was initially drafted too rigidly.

No DA in the five boroughs, he said, is ”looking to go back to pre-2019 era discovery laws where things were not required to be turned over [until] right before trial. We all agree that this information must be exchanged as quickly as possible.”

His push here relates to a talk Gonzalez said that he gave to new assistant district attorneys, some of whom, he said, seek out the Brooklyn office because of its reputation for reform: “You’re not here to be advocates. You’re here to do justice. Make the best decision you can on the case,” he tells the new ADAs.

And while this philosophy may not speak to those on the left as going far enough, Gonzalez said his electability is a sign that his approach is working.

“You look at some of the most progressive prosecutors across the United States,” he said. “A lot of them have lost their jobs or their offices are no longer doing these things. Brooklyn has continued to do things that are meaningful.”