Pillar subscribers can listen to this Pillar Post here: The Pillar TL;DR

Hey everybody,

It’s a Tuesday in Lent — we’re almost to Holy Week — and you’re reading The Tuesday Pillar Post.

When he was 17, Blessed Solanus Casey — then he was still called Bernard Casey — moved from his family farm in Wisconsin to the small river town of Stillwater, Minnesota, where his uncle was a priest.

Bernard stayed with an aunt and (different) uncle, worked in a brickyard, on streetcars, and as a guard in the Minnesota state prison where men from the Jesse James gang were incarcerated.

In fact, at the prison, he befriended two men — brothers — who had robbed banks, and trains, and stagecoaches with Jesse James, until they were caught and sent to the penitentiary. One of the brothers even made his young guard a trunk in the prison workshop, which Casey seems to have eventually taken with him to seminary.

Where the prison once stood, in a deep ravine along the river, is now fancy apartments and some stores, and I suspect most of the residents don’t know about the holy young man who once stood guard there.

But up the hill still stands the little white wooden sided house where Casey lived as a teenager with his relatives. I had occasion to be in Minnesota last week, so I snapped a picture for you all.

In the late 1880s, that electric line would not have been there, but I’m told the house otherwise looks much the same — and the windows up on the second floor were Casey’s room.

A few miles away is St. Michael’s, the parish church where Solanus was confirmed. Today the parish has a few relics of the holy priest, and a beautiful Solanus stain glass window (interiorly mounted and backlit).

If you look closely, you’ll see a little bee in that photo, behind Solanus’ right arm. It’s there for two reasons.

One — the man who donated the window was called “Buzz,” by his friends.

Two — There’s a story about Solanus, when he was a much older friar, being called out to the friary garden to help with a beehive on the verge of swarming.

As the story goes, Fr. Solanus started talking to the bees, telling them to calm down, and witnesses who were there say it worked, that the bees did calm themselves down and go back into the hive. Then, as it’s told, Fr. Solanus reached his hand into the hive, with no smoke or nets or gloves, and diagnosed the problem: the hive had two queens, prompting an apian civil war!

Blessed Solanus, apparently, took one of the queens, put it in his pocket, and resumed talking to his fellow Capuchins.

Is the story true? Well, it’s recounted by at least one Franciscan who says he saw it, not in medieval Europe or the deserts of the early Church, but in Indiana, in the 1950s. And there are lots of stories about animals sensing and responding to holiness. And grace builds on nature, and Solanus grew up farming so, yeah, I think it could be true. And I hope it is.

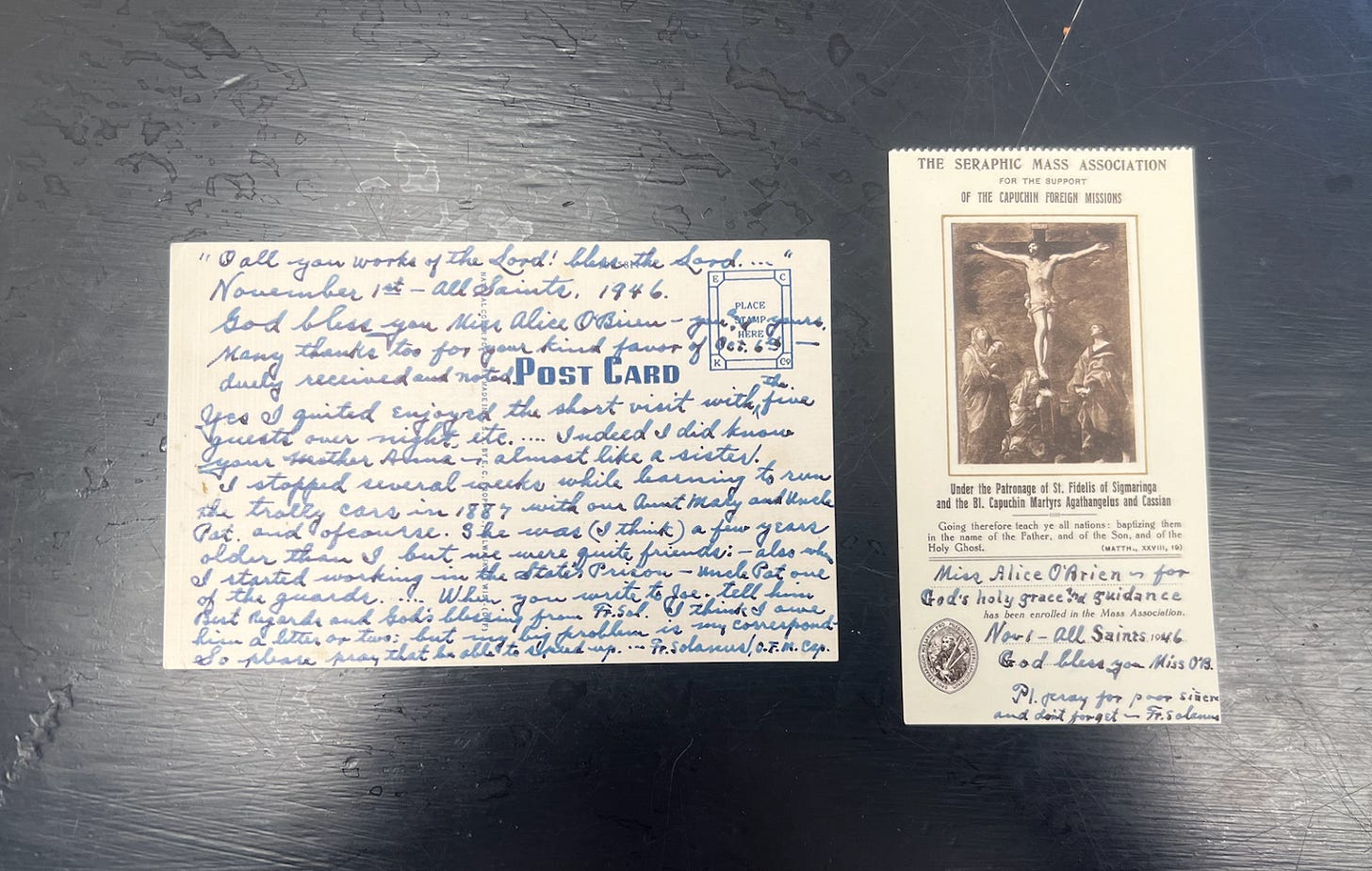

At the parish in Stillwater, the pastor also has a postcard and a little Mass card Solanus wrote in the 1940s to his Minnesota aunt. He let me hold them in my hands. It’s an experience I won’t soon forget — especially if Blessed Solanus becomes eventually St. Solanus.

Anyway, I was struck in Minnesota by the ways saints live amid the ordinary circumstances of their times and places. And it seems to me that the holiness of a saint can sanctify a place in some ways, too, leaving behind a kind of living memory of God’s extraordinary grace, and extraordinary kinds of cooperation with it.

But at the same time, that memory is fleeting, and held after a century or so only in the most extraordinary cases, and only then by the most devout.

To everyone else, we’ll likely be forgotten, the landmarks of our lives becoming fancy apartments, like that prison, or looking like ordinary little white hilltop houses to most passersby.

Few of us will be remembered in the towns where we spent time in our youths. If that were all we could hope for — that our memories be preserved — we’d have very little hope indeed.

But the only thing that really finally matters is to be a saint, and that’s true for all of us. The good news is there’s still time this Lent to repent, and to share more deeply in God’s life.

May Blessed Solanus Casey intercede for us.

The news

Villages have been bombed or burned, human rights activists have been detained and tortured without charges or trial. And the small minority of Catholics in the country have been forced from their homes, seen their churches destroyed, and been left in intense poverty.

In that context, freelance journalist Antonio Graceffo has the harrowing tale of a priest with a target on his back — and a people living their faith, and hoping to live free, in a crisis beyond imagination.

Read this story, guys. You don’t want to miss it. And pray for the people of Burma.

—

The Pillar investigates!

We don’t have numbers for the situation now, but we know that the pension fund liability has grown significantly in the past 10 years. And we know that there have been no concrete efforts to remedy the problem during that time, despite warnings and proposed solutions.

In fairness, we don’t know what percent of the pension obligation 1.4 billion represents. But we know it’s a big enough sum that the pope has warned “the current system is not able to guarantee in the medium term the fulfillment of the pension obligation for future generations.”

So what does this mean? That the Roman curia and Vatican city state will not be able, probably, to meet promised retirement obligations to employees, and fairly soon. That will be a monumental crisis — and without the benefit of compounding interest over years and years, an extremely expensive one for anyone who tries to bail it out, if anyone cares to.

The people who suffer will be the lay and clerical pensioners of the Vatican city state. Period.

Meanwhile, I hear joking to the effect that the Church should have a kind of Department of Vatican Efficiency, charged with identifying waste, consolidating expenses, and strengthening the financial future.

We did. Two of them, working in tandem. With people much more competent than Elon Musk and his merry band of gamers.

One was called the Secretariat for the Economy, and it was led by Cardinal Pell. He’s no longer in the role (God rest him) and the department has been reduced to a Potemkin dicastery, at best.

The other one was called the Office of the Auditor General. It was led by a man named Libero Milone. He’s now suing the Vatican for wrongful termination, charging that Cardinal Becciu had him fired for the egregious offense of doing his job. The lawsuit is, uh, not going too well.

The question is whether we’ll have such an effort again, empowered to help steer the Curia away from the financial cliff. Or at least figure out some seat belts or something.

And the bigger question is what the Vatican will look like in 10 or 20 years, when its credit’s been spent. There will be real changes in store for the Roman curia, out of necessity, not desire. But changes nonetheless.

As the final document came up for a vote, participants posed scads of amendments — enough to bring the proceedings to a halt. Organizers now say they’ll draft a new document, to be debated and considered at a follow-up session in October.

Well, in the end, you know what they (probably) say in Italy about stuff like this:

When the moon hits your eye

Like a big pizza pie, that's synodality.

—

We told you on Saturday that we’re beginning to feature some columns and commentary at The Pillar, by the popular demand of our readers, and to help Catholics engage — with smart sanity — in the conversations about real issues we’re having today.

In truth, “smart sanity” probably describes best our editorial policy on commentary, and the reason we’ve launched a “columns” section in the first place — because try as we might, we can’t find many repositories for smart sanity right now, for Catholics to talk reasonably through the issues we’re facing without reduction to absurdity, predictability, or insanity.

We’re excited to try this, in a way that compliments The Pillar’s mission as we grow into a broader community, and a broader journalistic project.

And we’re really excited that our first column was some both smart and sane — former congressman Dan Lipinski — a Catholic worth reading.

The bishops, arguing that those endowment should be better regulated, made big waves in the country, with one Indian journalist saying that support for the Modi government initiative “may have permanently soured Christian relations … by backing the country’s Islamophobic government on a controversial bill that Muslims see as a direct blow to their ancient codes.”

In a country where both Christians and Muslims constitute very small minorities, that could have lasting effects for both groups in the country.

So what happened? Why does it matter? And why did the bishops get involved?

The new rules ban foreign nationals from common worship with Chinese citizens, and require all visitors to affirm the national independence of Chinese Churches and faith communities.

To observers in the country, the new rules were likely aimed at creating a “pretext” for arresting foreign nationals for religious activity.

And of course, all of this suggests that six years after the Holy See’s accord with China, the Church faces less, not more, freedom to operate in China.

In his later years, McCarrick apparently suffered from such sufficient dementia as to prevent his participation in two criminal trials against him — one in Wisconsin, the other in Massachusetts. In light of that, I’ve seen a lot of Catholics express hope that McCarrick repented before he lost his mental faculties. That’s led me to some questions about aging, the soul and mental acuity, and I’m going to try and interview a moral theologian about that this week.

Meanwhile, it’s time to ask what the McCarrick scandal actually meant for the Church.

When it began five years ago, it was my perception that the scandal of McCarrick’s abuse toward minors, seminarians, and young priests would fundamentally change the Church. In truth, it fundamentally changed me: It began in me a new awareness about the relationships between power and coercion, and especially about the abuse of adults in the Church.

In those first few months, as McCarrick unfolded in the press, and the Pennsylvania grand jury report echoed across the country, bishops seemed to understand that for many Catholics, a sense of revulsion had been awakened — that they simply couldn’t believe the degree to which institutional self-protection and studied incuriosity seemed to allow for moral depravity without clear consequence in the Church.

We’ve since had many scandals, on a global level, pointing to an issue in need of resolution: That while we had already mechanisms of procedural accountability for priests and deacons — even if administered unevenly — we had precious little to address allegations of abuse, misconduct, or administrative negligence on the part of bishops themselves.

It became expected in those early months for bishops to take up promises of accountability and transparency — those became the watchwords of the day in 2018, and have continued to be in ecclesiastical fashion until today.

But in the U.S., episcopal commitment to an open style of ecclesiastical governance reached a high point on the exact same day it became clear that it couldn’t possibly last.