Moreton Bay was established first as a penal settlement in 1824 before it was thrown open to free settlers in the early 1840s, eventually becoming the town of Brisbane. Imagine new settlers arriving from the United Kingdom, mainly Irish and Scottish, to take up new pastoral leases with limited possessions. This is where my ancestors enter.

They brought herds of cattle and sheep from inland New South Wales via what we now know as the Darling Downs and descended via Cunningham’s Gap onto the rich country of the Brisbane River valley. They had few possessions, materials and tools, and there were no hardware shops on the frontier, but undoubtedly an axe, a crosscut saw and an adze were in their toolkit. How did they build their first houses? By observing other settlers’ houses and Aboriginal construction technologies. The ingredients were bush poles, stringybark sheeting, timber battens, all held together with grass fibre string. All of these materials were procurable from local Jagera Aboriginal people, who traded (or sold) materials and provided construction labour to the new settlers.

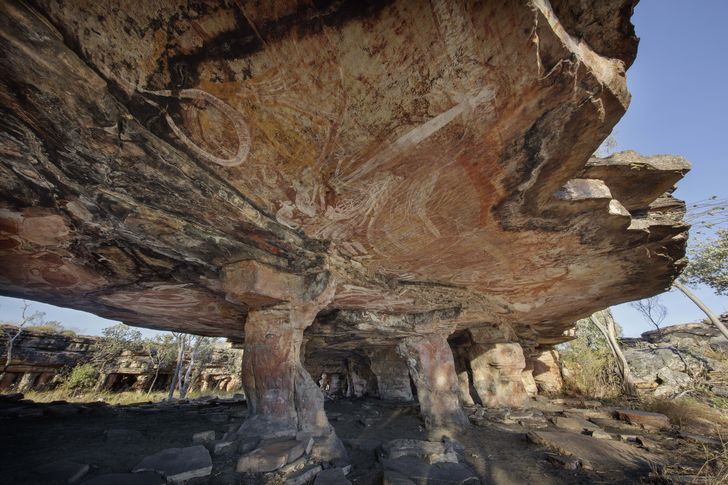

This transfer of sustainable construction techniques from Aboriginal culture into Anglo-Celtic immigrant culture was characteristic of the colonial frontier. First Nations people traditionally used all bush materials, including poles, stakes, foliage, palm fronds, lithes, vines, grasses, bark sheets, stone and soils, in developing their distinctive regional ethno-architectures.

The interested reader is referred to my book Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley for descriptions of the various architectural and engineering applications of these bush materials. It also contains references to contemporary Aboriginal groups who still use bush materials despite residing in conventional Western housing. And where better a place to start our analysis than with how such peoples value their bush material building traditions today? Examples in the book include the Yolŋu harvesting stringybark sheets in the Top End for cladding; the Lardil building windbreaks of local beach materials for recreational beach fishing camps on Mornington Island; the Girramay maintaining the practice of rainforest cane dome construction for tourism attraction at Jumbun (near Tully, Far North Queensland) and the Olkola use of Corypha cabbage palm leaves to protect barbecue fires from light rain in the tropics.1

What are the possibilities for contemporary architects to use biodegradable bush materials in a sustainable way for design projects? Let us start with what is actually happening in this field, particularly in rural and remote locations. Bush poles and posts are encountered commonly enough. Aside from a number of applications including fence posts, they are also essential components for bough sheds (also known as “bough shades”) which are clad with foliage – the preferred genus being spinifex due to its longevity. One of the most sophisticated spinifex bough sheds has been recorded in the Kimberley and comprised spinifex roof and wall sandwich panels 100 millimetres thick in chicken wire. Water reticulation through perforated pipes over the walls provided a slow dripping to create an evaporative cooling effect.2

Architectural researcher Tim O’Rourke has written at length on bough sheds and windbreaks, describing them both as the archetype Aboriginal shelters employed right across the continent. He concludes:

“Windbreak and shade structures built in the twenty-first century clearly reference the forms and functions of pre-colonial structures. In either the curtilage of a camp or within the fenced yard of social housing, the two types of shelter chronicle a preference for living around, rather than inside, enclosed dwellings. Despite the sustained use of housing by the state to change the behaviour of Indigenous Australians, the persistent use of the two traditional shelters enabled and maintained distinctive forms of Indigenous sociality.”3

O’Rourke points out that, historically, “The continuity of traditional structures in town camps and mission settlements in the 1970s offered a stock of vernacular precedents for architects seeking to design more culturally appropriate Indigenous housing … [and] knowledge of the adapted traditions is still relevant to how architects and governments respond to the social and environmental parameters of an ongoing crisis in housing for Indigenous Australians.” O’Rourke is talking of the continuity of these archetypes in Aboriginal communities, albeit with occasionally adapted material solutions. But what of the continuity of material use?

The early work of architect Paul Haar is most relevant to this point. He worked with a number of clients seeking self-help housing in Queensland, the Northern Territory and Victoria, co- designing and co-building their individual houses and utilising local bush materials. For example, at Mt Catt homeland in Arnhem Land, the Aboriginal residents had an intimate knowledge of their environment and its materials, and, working with Haar, chose to build with bush pole construction, stone infill walls, antbed floors and earth bricks. Haar provides an instructive demonstration as to how contemporary architects could be learning and applying knowledge of traditional bush materials.4

Another significant exemplar is the spinifex project of the Myuma Aboriginal group on the upper Georgina River. Led by Elders of the Indjalandji-Dhidhanu people, who have a sophisticated commercialisation enterprise established with the Australian Institute for Bioengineering and Nanotechnology at the University of Queensland, it involves the extraction of minute but strong nanofibres from spinifex grass. The project was originally inspired by the traditional use of spinifex cladding on domes in the dry interior. However, the discovery of the greater applications of the nanotechnology has seen the project expand a long way in the past five years, with a multitude of applications found – the latest, at the time of writing, is the use of the biodegradable spinifex nanofibres to provide safer injectable face gels.5

Spinifex grasslands conservatively cover 27 percent – and possibly as high as 40 percent – of the continent. The 69 species could potentially be yielding important materials for Australian building sites, their properties having already been well-researched by engineers. If the harvesting of spinifex can be sustainably managed, these grasses could be used by contemporary architects and further refined for building applications (for example, with the addition of an anti-flammable chemical agent to ensure fireproofing).6

Roof thatching with blady grass (Imperata cylindrica) is another material worthy of mention. Once commonly used for dome cladding along much of eastern Australia but recorded in detail in the north-east rainforest region, blady grass is so effective as a roof thatching technology that it continues to be used for roofing across many parts of South-East Asia, including for tourism facilities such as those seen in Bali. 7

Let’s turn to stone as a building material. In the early 2000s, I visited the Tyrendarra lava flow region in western Victoria. It was in this region that the Gunditjmara people had been building their basalt stone windbreaks and dome walls in the 1800s, a tradition that went back millennia earlier.8 In parallel, I observed that there was a prominent dry stone wall construction practice with this basalt at many of the local farming and pastoral properties, visible from the side of the road. Colonial settlers had robbed the Gunditjmara stone structures (and their technology) for walls on their own properties, though similar techniques would have been well-known to some of the new settlers from various parts of their homelands in Scotland and England. Nevertheless, the settler adaptation of Indigenous materials and practice clearly demonstrates the potential of dry-stone wall construction as a possible element in contemporary building projects where local stone types are readily available – for example, as walls to demarcate boundaries and subdivisions of properties.

It is clear that a range of bush materials are available for architects to adapt and test in contemporary design contexts, including bush poles, stone, soil, spinifex and blady grasses, and many others. More innovative practice is to be encouraged in this regard, not only by private architectural firms when carrying out individual projects, but by government departments in formulating their briefs for public projects.

– Professor Paul Memmott AO is an anthropologist and architect from the Aboriginal Environments Research Collaborative, School of Architecture, University of Queensland. His career has spanned more than 50 years encompassing the cross-cultural study of the people-environment relations of Indigenous peoples with their natural and built environments.

1. Paul Memmott, Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley: The Aboriginal Architecture of Australia (Thames and Hudson, 2022), 56, 106, 160, 181.

2. Paul Memmott, et al., “Nanotechnology and the Dreamtime knowledge of spinifex grass” in Caroline Baillie and Randika Jayasinghe (eds), Green Composites: Natural and waste-based composites for a sustainable future (Woodhead Publishing, 2017), 181–198.

3. Timothy O’Rourke, “Adaptive uses of traditional windbreaks and bough shades for Indigenous housing in Australia,” in Paul Memmott, John Ting, Tim O’Rourke, Marcel Vellinga (eds), Design and the Vernacular: Interpretations for Contemporary Architecture Practice and Theory (Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2023), 105–116.

4. Paul Haar, “Community Building and Housing Process: context for Self-Help Housing,” in Paul Memmott (ed.), Take 2: Housing design in Indigenous Australia (Australian Institute of Architects, 2003), 90–97.

5,6. Memmott, et al., 2017

7,8. Memmott, 2022

Source

Discussion

Published online: 31 Mar 2025

Words:

Paul Memmott

Images:

Clinton Weaver,

John Gollings,

Photograph: Howard Hughes. Courtesy of the Australian Museum Archives (AMS391/M00067/3),

Rodger Barnes

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2025