How some Sebastopol schools are dealing with the threat of ICE

The high school district is drafting a safe-haven policy, but other schools wonder whether that will simply put a target on their back

With reports earlier this month of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents in Sonoma County, some Sebastopol schools are reiterating their policies, procedures, and discussions on what will happen if ICE comes to campus.

Keri Pugno is the superintendent of Gravenstein Union School District, which oversees Hillcrest Middle School and Gravenstein Elementary.

“Yes, there’s a lot of fear, a lot of concerns, and a lot of question marks. It’s the what ifs—that’s what our staff, our front office, the teachers and parents are worried about,” said Pugno, who has been with the district for 24 years.

“The most important thing is that we really make sure that we have a strong process and strong policies that are in place and implemented consistently across the board at every school,” she said.

At Gravenstein Elementary School, any visitor must sign in to the front office, and that includes law enforcement and government officials.

“We don’t have these policies in place because of immigration—we have these policies in place to protect our students, protect our community and our campus. Therefore we’re just reinforcing that we have them,” she said.

One topic that has been brought up during discussions around immigration and schools is the idea of a safe-haven policy, which was often applied to churches and schools.

This January, according to the Council of Parent Attorney and Advocates (COPAA), “The Department of Homeland Security announced a new policy allowing immigration officers and agents to carry out enforcement actions—including arrests and searches—of undocumented immigrants in “sensitive locations,” including schools and churches. This new directive replaced a policy previously implemented in 2011, which had established that officers and agents of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) would not carry out enforcement actions at these sensitive locations except in limited situations.”

The website of COPAA also states that, “Under the newly announced policy of January 2025, those previous protections are no longer in place.”

With regard to safe-haven declarations, Pugno said, “The question that multiple superintendents, multiple schools, multiple officials were asking is, Does it change anything? Does it actually implement any change in practice? And the answer that I was able to perceive from it was, it doesn’t change our day-to-day.”

“It doesn’t change our abilities. It doesn’t change our rights, our students’ rights or anything there. Does it draw attention to it? Yes,” she said.

Pugno questioned if the school and district would be giving a false sense of security and safety when they couldn’t back it up.

“We really need to make sure that we are being honest and transparent and very straightforward,” said Pugno. “We are going to do everything possible to keep the campus a safe place for all of our students.”

She has also analyzed the school attendance to see if there was an impact or correlation with immigration raids and rhetoric in the news with daily attendance at the school.

“Was there an impact? No, not on our campuses,” she said. “That, being said, we have less than 15% of our campus being English learners, but that doesn’t necessarily equate to immigration status.”

Chuck Wade, the principal of Analy High School, is keenly aware of the impact that recent changes in immigration enforcement are having on his school.

“I think it’s enormously impactful to the mental health of a lot of our adults and students, in particular, our students and families of color, regardless of their immigration status. How people might worry about being perceived or treated—just the sort of shadow of that hanging over folks—is very real,” said Wade.

Wade said the school has created a specific flow chart related to immigration or ICE agents on campus.

“We’ve created sort of a bullet list that gives sort of additional instruction and support, and we put together resources and created binders that go to each of the entrances of our campus,” said Wade.

“We as educators… have to take it very seriously and recognize that whether or not we have ICE agents on our campus or in our community, this is hugely impactful to the mental health of our students and families,” he said.

Wade said he couldn’t find or point to any data that would support a recent fall in attendance due to the threat of stepped-up immigration enforcement.

“I’m not sure it really impacts our attendance, but I can’t imagine it’s not in the back of people’s minds,” he said.

“We’ve talked about it and speculated on how this would impact people. Anecdotally I’ve heard from some of our families that they’re a little more careful about where they go, even though their immigration status might not put them in jeopardy,” he said.

“We’re updating our safe haven resolution that was first introduced by the board in 2017 during the first Trump administration,” said Wade. “We’ve been working on updating that to signal to our students and families that it’s a priority for us that they feel safe and supported.”

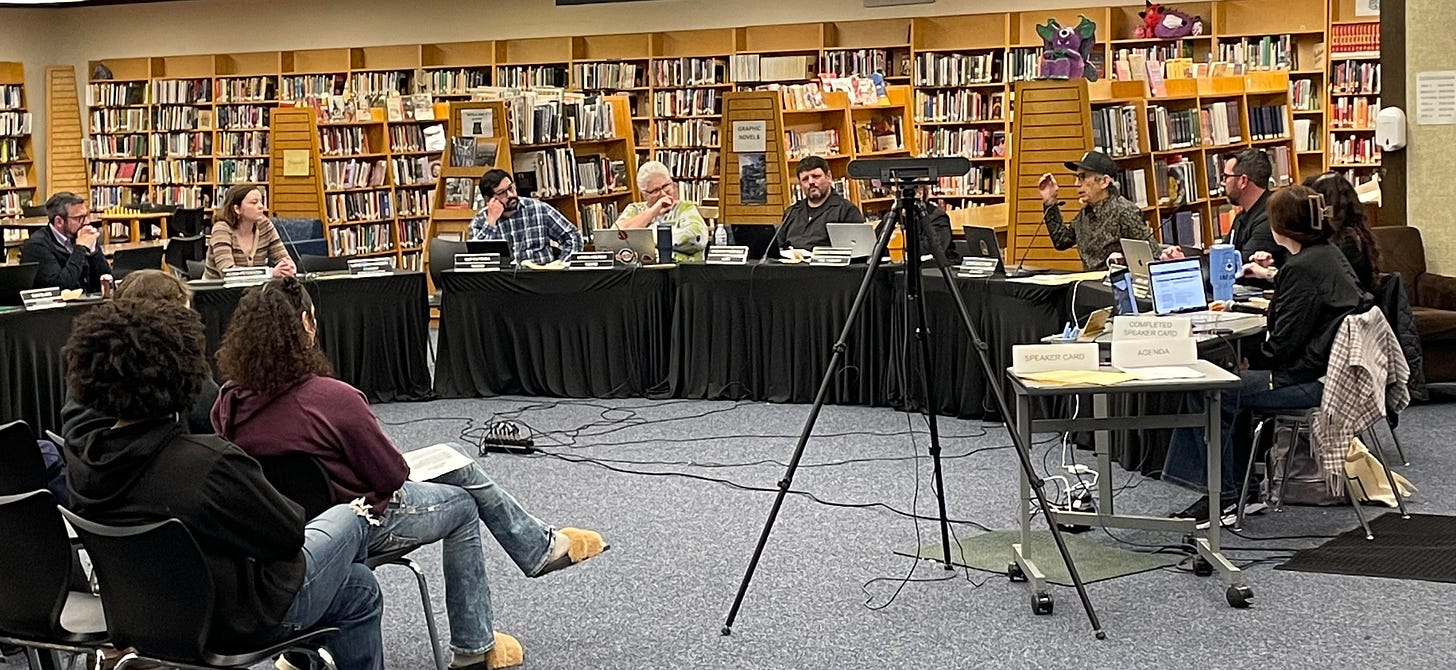

Earlier this month, the West County Union High School District board meeting had a discussion about introducing a safe haven resolution.

The conversation again revolved around if the designation would make the school and campus community feel safer and if it had any institutional power or effect—or if it would simply make the district a target on the map.

“Many families are living in fear, and many other families would like to learn how to become allies,” said Analy alumni Daniela Kingwell during public comment.

“It would be a tragedy if even one of our community members were taken away by Immigration and Customs Enforcement,” said Kingwell, “I personally spoke today with administrators at Sonoma Valley, Santa Rosa City Schools and Petaluma City Schools, who all confirmed with me their renewal of safe-haven policies. I encourage this district to look at the safe-haven resolutions that are attached to the agenda for this board meeting and to renew our resolution.”

It was apparent in the meeting that the issue wasn’t seen in simple black-and-white terms.

“I find myself pulled in two directions on this, in terms of publicly posting a document with the name “safe haven,” which can be scraped up by DOGE or the administration, and whether we’re not being skillful enough in implementing these things that we feel strongly about, but without making it such a target,” said WSCUHSD Board Chair Lewis Buchner

“I don’t know whether I’m just being paranoid or not, but I believe very strongly that we need to have this policy, and we need to really make sure that we implement it and we teach it,” he said.

The board agreed to discuss and review the Safe Haven resolution and to bring it up at the next board meeting. The board handed the review and drafting of the resolution over to the district’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion committee.

Flomy Javier Diza is a lawyer at Reeves Immigration Law Group and media liaison for the American Immigration Lawyers Association.

“I haven’t really seen any major news about ICE going in the schools,” said Diza, “There might be some remote areas, not in California, but it’s just the rhetoric that this administration is doing about hospitals, churches and schools.”

What is more commonly the case, he said, is ICE raiding a residential home. The reason why ICE historically has avoided schools is simple: it’s bad PR.

“They usually do it early in the morning, where they’re waiting for people to go out. These are undetected,” said Diza.

“I have many—probably more than five—US citizens who’ve obtained the Green Card already and become a citizen, who still call up for a consultation to see if they are safe,” Diza said.

They’ve obtained the Green Card legally but are worried about traveling now within the US and especially traveling outside the US,” he said. “They call just because they fear that they won't be able to come back.”

“The level of anxiety is really high. You can feel it,” he said.

Eric Wittmershaus is the director of communications for the Sonoma County Office of Education.

“We don’t actually set policies for what school districts will do if an ICE agent comes to their school,” said Wittmershaus. “We provide them information that they can use to set their [own] policies.”

“Ultimately, the decision on how to respond to an immigration enforcement action is made by the individual school district,” he said.

Principal Shawna Whitestine of Twin Hills Middle School said, “We are following the guidelines provided by SCOE.”

Wittmershaus said what is often seen is enforcement actions with ‘official looking’ documents that are far from it.

“A document that might call itself a warrant or something that’s signed by the ICE agent themselves, or something like that—they don’t carry the legal date that a signed order from a judge would carry,” he said.

“We see one of our roles is to educate folks in what those different types of warrants could look like and in the types of responses that are appropriate to take to them,” said Wittmershaus.

“US law says that all students in this country, school-age children have a right to attend public school, regardless of immigration status. As educational institutions, it’s important that we take steps to make sure that the children receiving an education are taken care of and have access to a quality education,” he said.

Wittmershaus also noted that immigration status and citizenship are considered to be protected characteristics in California, for purposes of discrimination and equal-protection law.

“The state has made it clear that this isn’t an issue that the state intends to just roll over on,” he said.

“We have our laws for a reason. They were passed by the legislature that was elected by voters, and they're going to defend them. While there’s that legal ambiguity, again, and this is a choice at the district level, generally, our position is that we follow state law here,” he said.

Wittmershaus said that he knows many of the schools in Sonoma County have encouraged families to be mindful of listing emergency contacts for their students, particularly in the event of a parent or guardian being deported or taken into custody.

“That’s also part of the reason that you see leaders at the state level, as well as you know our position here at SCOE, really wanting to do everything that we can in our power to legally reassure families that our priority is their children’s education and that they have stable environments that support learning,” Wittmershaus said.

“This kind of atmosphere right now around immigration and the sense of fear that’s out there—that can create an impediment to learning,” he said.

Wittmershaus reiterated that if an ICE agent comes to school and has a judicial warrant, schools will generally have to comply with that warrant.

“Students really learn best when they’re in a learning environment where they feel safe and supported by the adults around them,” Wittmershaus said. “It’s harder to focus on what you’re learning in math class that day if you’re worried about the status of a parent or a family member…It’s one other factor that represents a potential disruption to learning, and I think it’s really important for our community to be aware of that.”

Albert Levin is the editor of the Sonoma State Star and is currently an intern and reporter for the Sebastopol Times.

Pat, you’ve got it all wrong. These students are not criminals. Most were born right here in Sonoma County. They are trying to get an education.

Thanks for this article!