The Dark Underside of Representations of Slavery

Will the Black body ever have the opportunity to rest in peace?

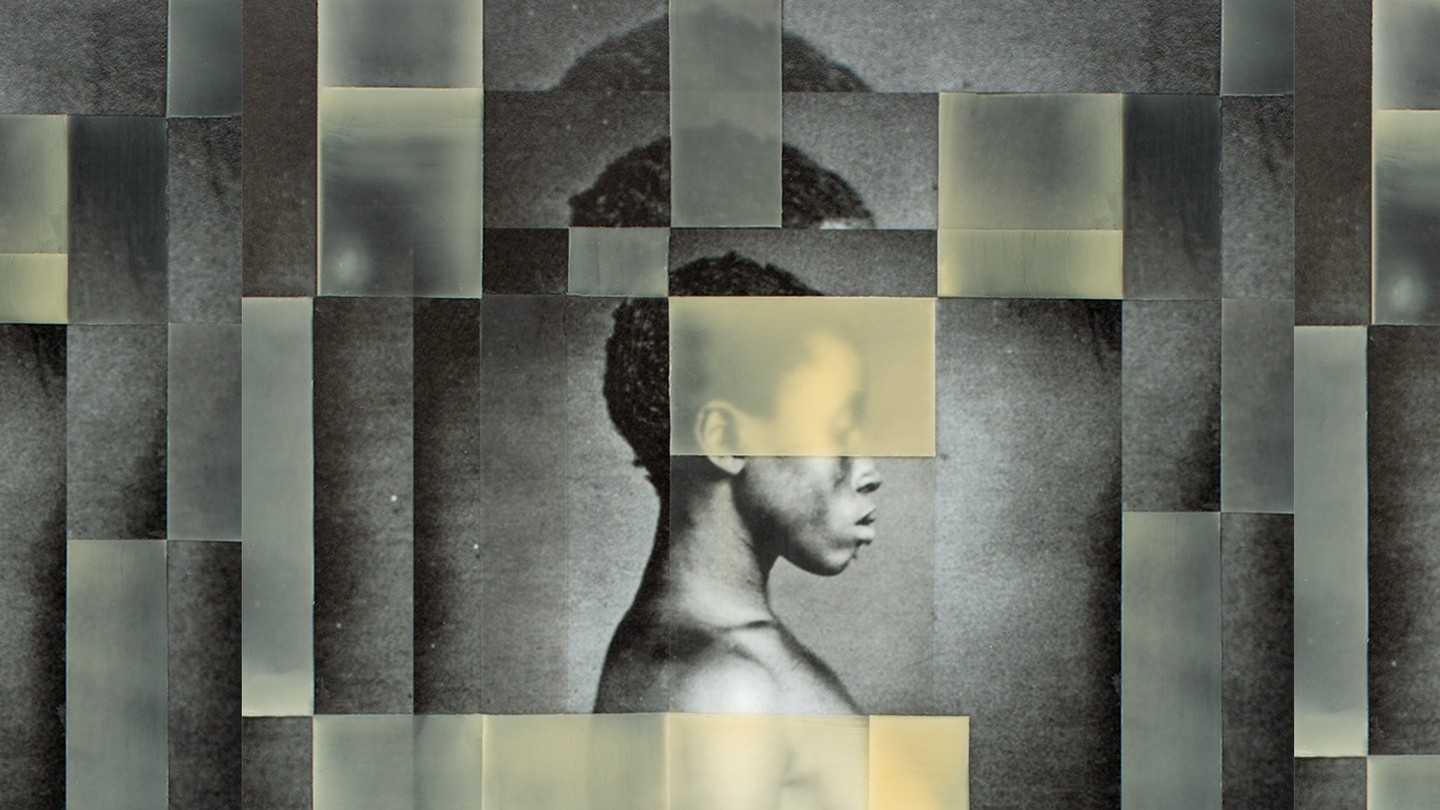

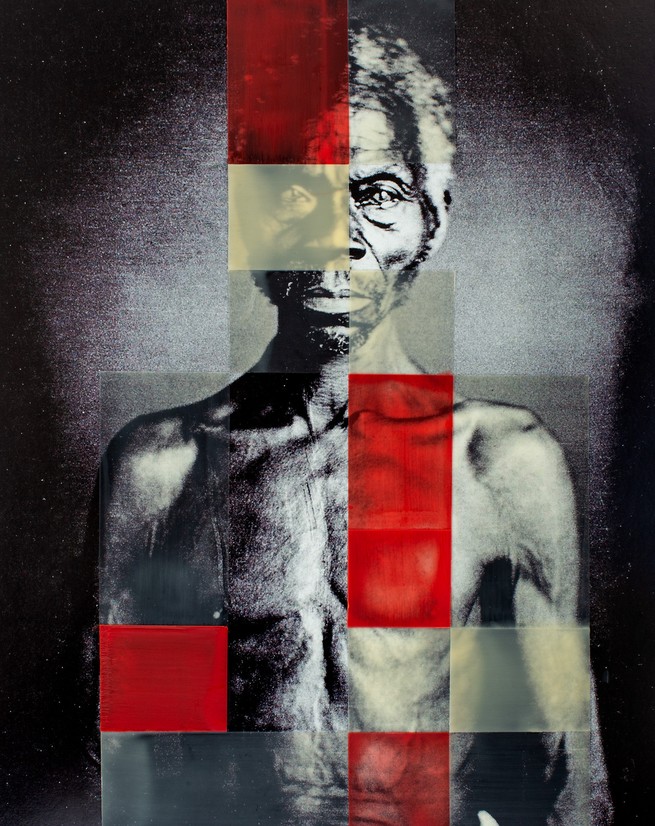

The photographs are about the size of a small hand. They’re wrapped in a leatherette case and framed in gold. From the background of one, the image of a Black woman’s body emerges. Her hair is plaited close to her head, and she is naked from the waist up. Her stare seems to penetrate the glass of the frame, peering into the eyes of the viewer. The paper label that accompanies her likeness reads: Delia, country born of African parents, daughter of Renty, Congo. In another frame, her father stands before the camera, his collarbone prominent, and his temples peppered with gray and white hair. The label on his photo says: Renty, Congo, on plantation of B.F. Taylor, Columbia, S.C.

In 1850, when these images were captured, the subjects in the daguerreotypes were considered property. The bodies in the photographs had been shaped by hard labor on the grub plantation, where they’d spent their lives stooped over sandy soil, working approximately 1,200 acres of cotton and 200 of corn. Brought from the fields to a photography studio in Columbia, South Carolina, each person was photographed from different angles, in the hopes of finding photographic evidence of physical differences between the Black enslaved and the white masters who owned them. A daguerreotype took somewhere between three and 15 minutes of exposure time, and the end result was a detailed image imprinted on a small copper-plated sheet, covered with a thin coat of silver.

Louis Agassiz, a professor at Harvard, commissioned the portraits of Delia and Renty, along with those of other enslaved people, from the photographer Joseph T. Zealy. The daguerreotypes remained, all but forgotten, in the school’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology attic until an archivist found them in a storage drawer in 1976. Since then, these photos of Renty and his daughter Delia have been featured on conference programs, in presentations, and reproduced in books.

As photography has moved from the scientific novelty of Agassiz’s time to ubiquitous contemporary entertainment over the years, the art form has reflected society’s inequity. The rediscovery of the daguerreotypes and their use in revenue-generating materials in the present day have helped surface an ethical issue that has long accompanied images of Black people’s bodies: Their presentation and exploitation still, in many cases, outweigh individual ownership and autonomy.

While the provenance of the photos traces a line from a drawer at Harvard to a photographer in South Carolina, their story today also has roots in Norwich, Connecticut, home to Tamara Lanier, who claims to be the great-great-great-granddaughter of Renty. As a girl, Lanier’s mother told her about an ancestor named “Papa Renty.” She learned that he was a master of the Bible and that, as an act of defiance, he taught other enslaved people to read. According to the history passed down through her family, Renty got his hands on Noah Webster’s The Original Blue Back Speller, and after tending to crops in the fields, he would study the book at night.

Lanier would not start searching for the truth behind those stories until 2010, the year her mother died. She began a genealogical search for her ancestors. She also told an acquaintance, Richard Morrison, of her mother’s death and her own attempt at tracing her bloodline. Morrison, an amateur genealogist, took what Lanier told him and did some digging. He came up with a name: Renty Taylor. Morrison’s Ancestry.com search pulled up a photograph of Renty from 1850—one of Agassiz’s daguerreotypes. Further searches provided Lanier with information about Agassiz and Zealy and mentioned where she could find the original pictures: Harvard University. When she traveled to the school and viewed the images, Lanier was disappointed by their size, which resembled a deck of cards. There he was, the man who seemed larger than life in many of her mother’s stories, looking small and sad.

Seeing her ancestors in the archives at the university, Lanier felt the portraits were out of place. She believed that the images of Renty and Delia belonged to her. So on March 20, 2019, she filed a lawsuit against Harvard. In her lawsuit she alleges that the images of Renty and Delia are still working for the university, based on the licensing fees their images command. (In 2019, Harvard acknowledged that the images are not protected by copyright and that it charges only a $15 fee for a high-resolution scan.) Lanier requested that the university grant ownership of the daguerreotypes to her, pay her punitive damages, and turn over any profits associated with the portraits. “From slavery to where we are today, Black people’s property has been taken from them,” Lanier told me. “We are a disinherited people.”

Related podcast: The short, uneven history of Black representation on television—from Julia to The Cosby Show to today’s “renaissance”

Listen and subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google Podcasts

Earlier this year, a court dismissed Lanier’s lawsuit, saying that “the law … does not confer a property interest to the subject of a photograph,” no matter the circumstances of its composition. Neither Harvard nor the judge presiding over the case disputed Lanier’s evidence that she was a direct descendant of Renty. Still, the court declared that Havard had the right to keep ownership of the photographs. Lanier has appealed the decision, and now the Massachusetts Supreme Court will weigh in. Oral arguments are scheduled for November 1.

Lanier’s case is about more than her personal interest in the photographs; rather, it has greater implications in a long-running reckoning. Agassiz used these photos of enslaved Africans, along with measurements of their cranium, as evidence of a theory known as polygenism, which was used by American proponents to justify slavery. He and other scientists believed Black people were created separately from white people, and their pseudoscientific inquiry was embedded into racist stereotypes in the bedrock of this country. To some historians, in keeping and curating images like these, Harvard is still celebrating the work of these practitioners and their discredited racial theories. (Harvard did not respond to requests for comment. In a previous statement, the university claimed the daguerreotypes were “powerful visual indictments of the horrific institution of slavery” and hoped the court ruling would make them “more accessible to a broader segment of the public.”)

The outcome of Lanier’s court case against Harvard will be legal commentary on whether the Black body ever has the opportunity to rest in peace, or whether present-day academic and entertainment priorities outweigh the rights of the Black deceased.

Whether she gets there or not depends on her long shot of an appeal. But her fight is an important front in a war over the ownership of images of Black bodies, one that is being waged on TikTok as well as in dusty archival drawers.

Harvard isn’t the only institution of higher learning charged with continuing to benefit from the exploitation of enslaved people. In 2019 Georgetown University announced a reparations fund for the descendants of the people Georgetown had enslaved, after acknowledging that the university had sold 272 enslaved people in 1838. Earlier this year, Brown University students voted to provide reparations in the form of preferential admission and direct payments to the descendants of enslaved people owned by the university’s namesakes and former leaders.

But Lanier’s case with Harvard is peculiar because it involves Black people who, she argues, still might be considered to be working for the university—albeit through their images after their deaths. To better understand this argument, first we must understand what the camera was designed to do.

In its earliest form, the camera was a scientific invention. To the operator, it was a recording device, a tool for visual measurement and accuracy that could create a truthful likeness. Unlike oil paintings, which could obscure blemishes, or caricatures meant to exaggerate certain features, the camera was meant to capture subjects as they were seen with the eye. But because cameras were seen as instruments of truth, photographs had immense potential to be used as propaganda.

“Images can be called on to do so many things,” Leigh Raiford, an associate professor of African American studies at UC Berkeley, told me. Paraphrasing the art critic Nicole Fleetwood, Raiford added: “Black skin is itself an icon, an image that stands in to mean a whole host of other things, that people can hang all of their own ideas on—a symbol to be both revered and venerated.”

Antebellum ideas about Blackness were informed by stereotypes depicted in the pervasive illustrations of Black men as either docile and subservient or violent savages, and the cartoons of Sambos—ink-Black skin, frog eyes, and overextended lips stained red. Or images of a cheery midnight-colored man with buck teeth eating a watermelon.

In an effort to fight these anti-Black caricatures, more than 150 years ago, Frederick Douglass started exploring photography as an avenue for liberation. He gave four lectures about the subject: “The Age of Pictures,” “Lecture on Pictures,” “Pictures and Progress,” and “Life Pictures.” Douglass believed that the ability to make pictures is one of the defining things that make us human. In his writings, Douglass asserts that for years white men held the authority to shape how the world was seen. Douglass’s particular attraction to the camera came from the ability it provided him to represent himself without the caricaturing hand of an artist. A photographer could not give him exaggerated lips or ignore his dapper attire. Through the eye of the camera, he could control how he was seen.

Douglass was the most photographed American man of the 19th century, and in his own life he saw the camera’s lens as a tool to help free Black people step into a new identity. In images of him, which were constantly reprinted in newspapers and promotional material ahead of his lectures, his face is always stern, unflinching. For many, his portraits were the blueprint for what Black freedom and dignity looked like.

Douglass wasn’t alone in his subversive use of the form. Sojourner Truth, an antislavery activist, sold cartes de visite—small cards fitted with miniature portrait photographs—to fund her speaking tours about emancipation. I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance, Truth had printed on the front of each portrait, her signature a testament to this portrait’s authenticity, functioning something like an early copyright. In the frame she is self-assured and unafraid, seemingly taking the trauma and sorrow she has known and giving them shape by standing in defiance of them, staring straight into the lens.

Unlike Renty and Delia, Douglass and Truth were able to document their life’s journey and disseminate their image at their leisure. Portraits of these abolitionists are some of the rare examples that we have of the transition from enslaved to emancipated people who have decided to make visual testimonies in their own image. In many ways their portraits were the apex of self-determination, giving other Black people hope and something to strive for in the future, while providing stark contrast to the dearth of liberties afforded to Renty and Delia.

But what happens when historical Black images are used or manipulated in ways that neither the subjects nor the photographers intended? One day in 2021, Lanier was tagged in a social-media post by someone she didn’t know. The post showed an animated image of Renty making lifelike movements within the vintage daguerreotype frame Lanier had already seen. She was shocked when she opened the image. She eventually called her two daughters to her computer screen. “Come and see this,” she said.

It turns out that the animation was created on MyHeritage, an online genealogy platform started in 2003 that allows users to search historical records for mentions of their forebears. The site has grown to include a genetic-testing service, MyHeritage DNA, as well as an app and several software products. MyHeritage also uses an artificial-intelligence software, which it calls Deep Nostalgia, to create realistic facial movements in a photograph. The site’s users can upload pictures of long-deceased relatives to the website, which then animates their ancestors with motions such as smiles, blinks, and head turns. The process is free (up to a certain number of animations), and, according to MyHeritage, users have created more than 90 million animations. In its Frequently Asked Questions section, the site tells users that the software “is intended for nostalgic use, that is, to bring beloved ancestors back to life,” and warns that it is not built for more nefarious purposes, such as creating “deep fakes” of living people. But other ethical issues are mostly left to the discretion of users.

Things might get out of hand, for instance, when people revitalize subjects who are not part of their own ancestry. One controversial usage of the software was in a viral montage posted to TikTok. The video is uncanny to watch. To the musical accompaniment of a remix of Andra Day’s “Rise Up,” a portrait of Emmett Till emerges and, without warning, his head begins to move, tilting upward as his eyes rove off-screen. Faces of people killed by racially motivated violence pop up one after another—Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice. Sandra Bland blinks directly at the camera. Michael Brown looks off to the side, wearing his high-school-graduation cap and gown, as if he is looking for his classmates, forever imprisoned in a reanimated frame.

The montage has been viewed more than 1.5 million times. The comments on the video run the gamut: One commenter wrote “cannot watch this”; another explained that the experience was too intense; and for others the video elicited tears. One person even asked whether family members of the victims had seen the video. The creator responded saying he wasn’t sure.

This isn’t the first controversy involving images of Till. His mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, made a deliberate choice to show his disfigured body in a 1955 open-casket photograph printed in Jet magazine, a Black-owned publication. The decomposed body of a 14-year-old Black boy shocked the nation, and was an indelible moment for Black readers of a certain age, but many white-owned newspapers thought the photos were too graphic to print and did not publish them.

But what differentiates this compilation is the camera’s ability to witness the brutality of white supremacy, in service of Black people. Photography gave voice to those who might not be able to have the opportunity to speak out; in the same way, the camera served as an avenue for Douglass and Truth to express their social standing, capturing Black people’s transition from being property to having agency and ownership over themselves.

Often a Black reality goes denied unless we have control of the publication and dissemination. Till-Mobley wanted the world to understand the torture that her son endured, and made the decision to share a devastating personal circumstance in the hope of galvanizing support for the civil-rights movement. Her willingness to share is part of the reason that Till is remembered today, but even his image is not off-limits when it comes to digital resurrection by MyHeritage’s Deep Nostalgia software.

This technology spawns a series of questions: At a time when Black bodies are treated as teaching moments for the larger culture, are those whose bodies were broken—by the whip of an overseer or the bullet of a police officer—ever afforded the opportunity to rest in peace? This inquiry is the latest curious development in the ethically fraught conversation about Black bodies, ancestry, and ownership. There is a direct line between historical exploitation and the ongoing commercialization of and profiting from images of dead Black people, over which their descendants often have little control, few claims, and few rights.

America is still grappling with the limitations of freedom, and whether Renty and Delia will be released from the grips of the archives remains to be seen.